In last week's Journal we looked at Bramley and how systems have changed in recent times.

This week we will look at the different characteristics of dessert varieties. Each variety exhibits individual traits.

Cox, our 'national' apple since the 1950's is by far the most difficult to manage of the varieties currently available on Supermarket shelves. It does have the ability to produce fruit on 'spurs' on semi permanent branches, or as part of a 'renewal' system where laterals grown on a main branch structure form fruit buds on 2, 3, & 4 year old wood before these units get to strong and are removed allowing new fruiting laterals to take their place. Cox does not naturally produce fruit bud on maiden (1st year wood) and on newly planted trees very often aborts the buds leaving 'blind' wood, this results in an area close to the tree stem devoid of any fruiting wood and as a result a significant area of the orchard does not bear any fruit.

Cox, our 'national' apple since the 1950's is by far the most difficult to manage of the varieties currently available on Supermarket shelves. It does have the ability to produce fruit on 'spurs' on semi permanent branches, or as part of a 'renewal' system where laterals grown on a main branch structure form fruit buds on 2, 3, & 4 year old wood before these units get to strong and are removed allowing new fruiting laterals to take their place. Cox does not naturally produce fruit bud on maiden (1st year wood) and on newly planted trees very often aborts the buds leaving 'blind' wood, this results in an area close to the tree stem devoid of any fruiting wood and as a result a significant area of the orchard does not bear any fruit.

Gala by comparison creates fruit bud freely on maiden (1st year wood) and this raises the cropping potential of Gala v Cox.

Braeburn is slow to grow away in the first year and can look very disappointing, but recovers quickly in the second year and yield is spectacular from an early age.

I will concentrate for now on COX

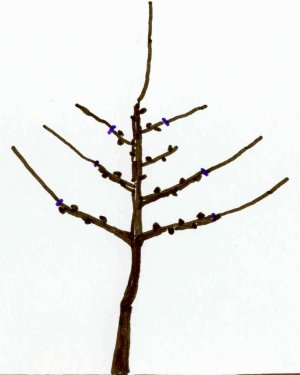

Ideally the young tree should start as a feathered maiden. e.g. with several young branches (feathers) formed in the nursery.

Ideally the young tree should start as a feathered maiden. e.g. with several young branches (feathers) formed in the nursery.

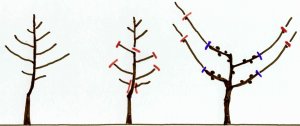

If the tree is intended to be trained as a 'centre leader' tree, remove only lower feathers leaving 4-5 feathers to form main base branches. Lightly tip; removing no more than 1/3 of centre leader. See red cuts

For a bush tree; keep only 4 feathers to form main branches and cut leader back to the highest retained feather. See red cuts!

Most commercially grown Cox trees have relied on a renewal system over the last 30 + years. By introducing carefully chosen new growth on the framework branches which will develop fruit bud during the 2nd years growth and allowing this new lateral branch to go unpruned until containment is required, fruit bud and subsequently fruit quality will be optimised. Once the new 'lateral' becomes too long (fills it alloted space) cut it back, either to the growth ring (the point where the last year's growth started, or to a fruit bud.

50 years ago it was commonplace to use a spur pruning system on Cox. Initially the tree would be shaped in the same way as I have described, building a permanent framework of strong structured branches and then as the natural establishment of fruit buds resulted in a 'spur' developing on the framework branches. To maintain a healthy spur capable of growing quality fruit maintaining the spur is very important. As the spur develops, young vegative shoots will emerge from the spurs. The 'lazy' approach results in pruners just cutting the new growth back above the spur, resulting in increasing vegative growth in subsequent years. Before long the spur can look like a porcupine with an ever increasing shaft at the base of the spur system. This is so wrong the spur should be renewed by initially cutting back to the growth ring (the point where the new shoot started) and as the spur develops with increasing fruit buds present on the spur, by 'shortening' the spur; e.g. reducing the number of buds. This strengthens the spur and improves the probability of a healthy flower and good quality fruit.

50 years ago it was commonplace to use a spur pruning system on Cox. Initially the tree would be shaped in the same way as I have described, building a permanent framework of strong structured branches and then as the natural establishment of fruit buds resulted in a 'spur' developing on the framework branches. To maintain a healthy spur capable of growing quality fruit maintaining the spur is very important. As the spur develops, young vegative shoots will emerge from the spurs. The 'lazy' approach results in pruners just cutting the new growth back above the spur, resulting in increasing vegative growth in subsequent years. Before long the spur can look like a porcupine with an ever increasing shaft at the base of the spur system. This is so wrong the spur should be renewed by initially cutting back to the growth ring (the point where the new shoot started) and as the spur develops with increasing fruit buds present on the spur, by 'shortening' the spur; e.g. reducing the number of buds. This strengthens the spur and improves the probability of a healthy flower and good quality fruit.

This system, though largely redundant on commercial farms due to labour cost, can be an ideal format in the garden. As long as the basic framework is accurately created and the fruiting spurs are managed correctly, this type of tree can be not only attractive, neat and tidy, but will be well placed to produce a quality crop.

Next week we will look at Gala & Braeburn Pruning

Take care

The English Apple Man