This week The English Apple Man attended two Technical Conferences: On Tuesday the AGROVISTA Technical day and on Wednesday the BIFGA Technical Day.

With a lot of subject matter for dissemination, The English Apple Man Journals will report items of particular interest over the next few weeks, but while waiting for individual Power Point Presentations to ensure justice is given to the quality of the presentations, this week the Journal will look at some interesting trials into ultra intensive apple growing systems in America.

Leslie Mertz reports in the latest issue of The Good Fruit Grower on research into high-density orchard systems.

Michigan State University researcher says high-density systems are where the money is!

Michigan State University tree fruit educator Phil Schwallier is assessing high-density orchards at the Clarksville Research Center in Clarksville, Michigan, to evaluate super spindle, two-leader, three-leader and tall spindle systems on five apple varieties. 2018 marked the first time he allowed the 4-year-old trees to fruit. Shown here are two-leader Gala trees in first crop, fourth leaf in September 2018.

"You think your life has changed?" asked Michigan State University tree fruit educator Phil Schwallier. "It's going to change more. You're going to higher densities and narrower systems. And you old guys? Let the young folks plant them closer together!"

That's how Schwallier started his talk on the benefits of high-density apple orchards at the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market Expo in December in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Regardless of the type of high-density architecture a grower chooses, he said, these systems have it all: higher yields, more uniform crops, excellent quality, better vigor control, improved opportunity for mechanization and the potential for far greater profits.

His glowing assessment of high-density orchards follows the 2018 results of an experiment he and his research group are conducting to evaluate super spindle, two-leader, three-leader and tall spindle systems on five varieties at MSU's Clarksville Research Center in Clarksville, Michigan.

The varieties - Gala, Honeycrisp, Macintosh, Jonagold and Fuji - are all on Nic 29 rootstocks. They planted them four years ago with 11- foot row spacings to accommodate their harvesting equipment, but Schwallier acknowledges that they could have planted them at least a couple of feet closer. Fall 2018 is the first time they allowed the trees to fruit.

The planting formats are listed below:

2,414 super spindle trees set 0.5 meters apart (2,414 leaders per acre) - (5,793 per hectare)

1,207 two-leader trees set 1 meter apart (2,414 leaders per acre) - (5,793 per hectare)

804 three-leader trees set 1.5 meters apart (2,414 leaders per acre) - (5,793 per hectare)

1,207 tall spindle trees set 1 meter apart (1,207 leaders per acre) - (2,896 per hectare)

In terms of bins of apples per acre, the super spindle system performed the best across all varieties in the first year of fruiting. This early high yield makes sense, Schwallier said, because all their energy went into a single stem during their first three years of growth. That allowed the stem to shoot up very quickly, "and now they're fruiting all the way down the stem," he said.

In terms of bins of apples per acre, the super spindle system performed the best across all varieties in the first year of fruiting. This early high yield makes sense, Schwallier said, because all their energy went into a single stem during their first three years of growth. That allowed the stem to shoot up very quickly, "and now they're fruiting all the way down the stem," he said.

In ensuing years, however, that lead will falter. Multileader trees take a bit longer to establish, but when they do reach full bearing (in about one to two more years for two-leader, and two to three more years for the three-leader), they will outperform tall spindle and super spindle trees, he said.

Schwallier added that multileader will perform best in the long run for three main reasons: 2D multileader systems can be planted at very high densities to have more stems per acre; almost all of their vegetative growth is fruiting wood and very little is structural wood; and all of the fruit will be very high quality.

In fact, when looking at apples per tree in this initial harvest at fourth-leaf, the three-leader system already came out on top, followed closely by the two-leader system: Gala at 54.2 and 51.1, respectively; Macintosh at 41.9 and 37.6; Jonagold at 27.4 and 25.8; and Honeycrisp at 20.5 and 16.4.

By comparison, the numbers of apples per tree for tall spindle were 47.8 for Gala, 36.9 for Macs, 17.1 for Jonagold and 15.0 for Honeycrisp; and for super spindle, the numbers were 35.9 for Gala, 21.6 for Macs, 15.6 for Jonagold, and 13.1 for Honeycrisp. Fuji was about even across all four systems, ranging from 30.1 for two-leader to 28.4 for three-leader trees.

In addition, Schwallier said, all the high-density systems in their 2018 trial yielded superior apples. "We had less than half an apple per tree (on average) that would not fall into the extra-fancy category," he said, and that included all the varieties, and both green and red strains of each. Schwallier plans to follow these trees for five to 10 years to see how well they do over time.

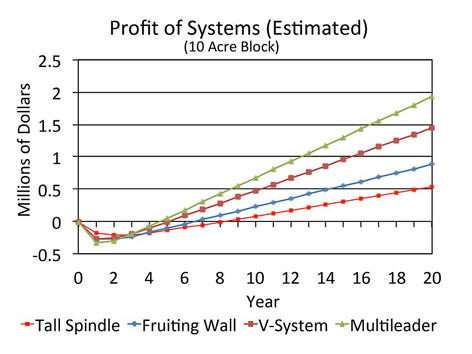

Beyond the first-year-fruiting data, he and his research group assessed costs of production and future profits for different systems.

According to their estimates, which were based on previous studies and approximations of current nursery tree costs, tall spindle will bring in about a $500,000 profit per 10 acres over 20 years, while apples grown using the V-system will yield three times as much. The top moneymaker was the multileader system.

"Once these trees get to full canopy, I think they can easily do 100 bins per acre, and probably even 150 bins per acre, so that's 2,000 bushels," he said. "And if we really increase density and go to 6- or 7-foot row spacing, you might get 3,000 bushels per acre every year, so you'll have $3 million per 10 acres at the end of 20 years."

Although high - density, multileader systems have a few drawbacks, such as slower a -nd higher - cost of establishment, the advantages far outweigh them, Schwallier said. In addition to higher yields and fruit quality, labor requirements are lower because multileader trees have no inside structure, except for the main leaders.

"It's easy hand pruning and easy hand thinning, and you can precisely thin the trees to whatever you want because they're so narrow - they're only a foot wide, so no limb bending is needed," he said. In other words, he said, workers have no complex pruning decisions to make and instead are tasked with simply removing the large limbs off the main leaders.

Another benefit of these essentially two-dimensional systems is that they will be far more compatible with mechanized harvesting because the fruits are readily visible and within reach, instead of being tucked into the canopy. Pickers can pick the whole tree from one side.

Regardless of whether growers are ready for the jump to high-density systems, they are the future of the apple industry, he stressed.

"Whether it's super spindle, fruiting wall, V-system, or whatever you do, you will be planting these systems," he said.

Leslie Mertz, Ph.D., is a long-time freelance science writer based in Gaylord, Michigan, and has been a regular contributor to Good Fruit Grower since 2015.

Leslie Mertz, Ph.D., is a long-time freelance science writer based in Gaylord, Michigan, and has been a regular contributor to Good Fruit Grower since 2015.

Apple growers may be thinking about trying high-density systems in their orchards, but they aren't finding multileader trees among the regular commercial nursery stock, according to Michigan State University tree fruit educator Phil Schwallier.

The big reason is cost. Multileader trees are more expensive to grow and nurseries charge a premium for them, but most growers balk at the higher per-tree price, he said. That is despite the fact that two-leader systems require half the number of trees per acre compared to single-leader systems, and three-leader systems require only a third, he noted.

Some growers, especially large orchard operations, have begun contracting with nurseries to grow multileader trees. "If you do, however, the nursery is going to want you to take all of them, so you get some good ones and you get some bad ones," Schwallier said.

"Beyond that, you get a pretty good charge with them, typically $3 more per tree or maybe even $4 per tree. Again, typical growers tend to not want to pay the price, so they back off."

So what's the average grower to do? More often they are turning to bench grafting their trees!

"The trend for this is growing, and I think that's because we're getting our densities so high and planting our trees so close that our orchard spacings are not much different from the spacings in a nursery," he said. "That means growers can bench graft a tree and plant it 'right in place' into the orchard."

To do direct planting well, the grower needs to get those tiny, bench-grafted trees onto a trellis and an irrigation system immediately, Schwallier said.

"You need to take extremely good care of these trees, because they are very susceptible to things like injury from machinery and herbicides, and from winter injury," he said. On the other hand, direct planting eliminates nursery shock and growth delays.

Schwallier estimated that about 10 percent of growers are bench grafting, and most of them are buying rootstock and hiring someone to come to the farm and graft it to scion there. That's up from about 4 to 5 percent a decade ago, he said.

"Of those who are bench grafting, most are just experimenting at this point, perhaps bench grafting 30 percent of their trees." As more growers see the value of high-density orchards, he added, "I think those numbers will only grow."

For more information on trials - Click on THE GOOD FRUIT GROWER website.

Readers will notice 'no mention of Brexit' but at the AGROVISTA Technical Seminar, this very clear picture of a very uncertain situation was illustrated:

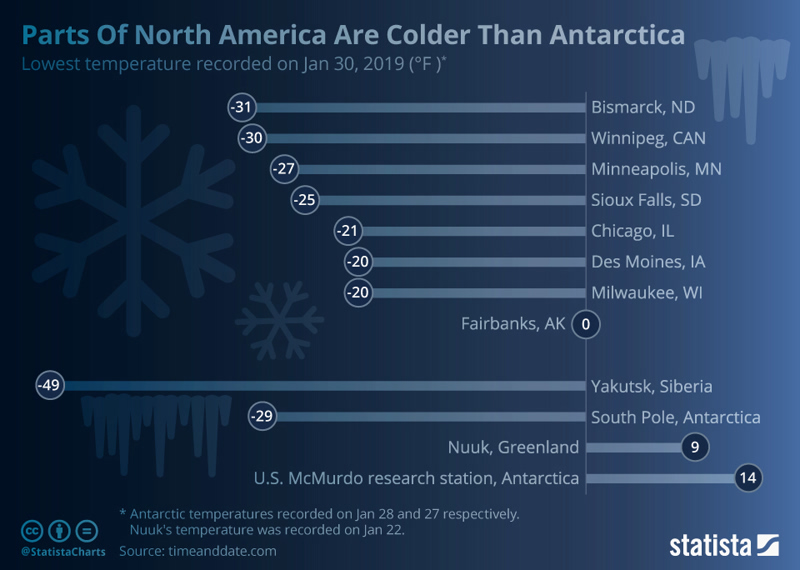

And, the cold weather is a topical subject this week; in the UK and more dramatically in parts of the USA.

That is all for this week

Take care

The English Apple Man