The seemingly inevitable drive towards bigger businesses via amalgamation, take-overs or sometimes organic growth is not confined to manufacturing or service industries.

This week The English Apple Man compares rationalisation in the USA and UK apple industries. Also is there a lasting place for the small volume producer.

The British apple & pear industry is dominated by a few very large fruit farms.

Larger farms, but fewer growers is a common theme - this story from Washington State which was reported in The Good Fruit Grower demonstrates that rationalisation is not confined to the UK fruit industry.

'It's happening to everybody': Stats paint stark picture of apple orchard consolidation.

Below: John and Sherry Kuntz

John and Sherry Kuntz pose in front of the site of their third-generation fruit orchard in August in Chelan, Washington. A year ago, the Kuntzes sold their share of the business to some nephews who may use it for wine grapes and vacation rentals and have been removing trees. The retired couple kept at least one tree of each variety for nostalgia's sake.

John and Sherry Kuntz pose in front of the site of their third-generation fruit orchard in August in Chelan, Washington. A year ago, the Kuntzes sold their share of the business to some nephews who may use it for wine grapes and vacation rentals and have been removing trees. The retired couple kept at least one tree of each variety for nostalgia's sake.

Though technically retired, John Kuntz still spent the 2019 fruit season getting up at 4:30 each morning to tend to what's left of the orchard he sold last year. Either he was hanging nets over his few cherry trees, thinning his apples or fixing water lines amid the holes and stumps of removed trees on his hillside apple orchard overlooking Central Washington's picturesque Lake Chelan.

Kuntz, a third-generation grower, and his wife, Sherry, still have their pretty view and a few hobby trees, but they are one of many small-acreage apple growers in the United States who have sold their farms, making way for the insatiable march of consolidation.

Orchards are few and large, and the trend is toward fewer and larger.

"It's happening to everybody," said Kuntz, 71.

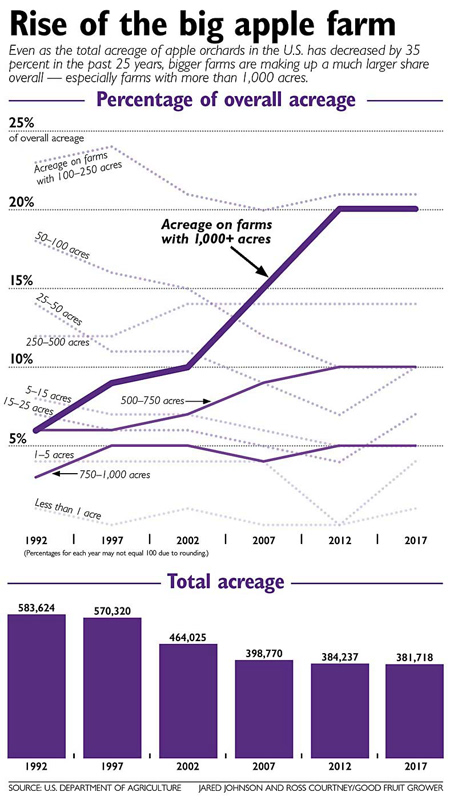

Indeed. None of this is surprising, but the latest ag census by the U.S. Department of Agriculture reveals stark new figures for a trend that dates back decades. In 2017, 35 percent of the apple acreage in the United States was on farms of 500 acres or more. In 1992, those farms represented only 15 percent.

The numbers deserve some caveats. The census counts growers with a fraction of an acre - hobbyists with just a few trees in their yard - as farms, skewing the acreage weight. Meanwhile, farming families face myriad decisions; trying to compete with larger farms is just one of them. But the curve has been moving for the past 25 years, indicating many growers are leaving the business because they have to, not because they want to.

The numbers deserve some caveats. The census counts growers with a fraction of an acre - hobbyists with just a few trees in their yard - as farms, skewing the acreage weight. Meanwhile, farming families face myriad decisions; trying to compete with larger farms is just one of them. But the curve has been moving for the past 25 years, indicating many growers are leaving the business because they have to, not because they want to.

"People don't necessarily exit a business because they don't like it, they exit the business because they can't make a profit from it," said Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association.

The causes

The association, which lobbies on behalf of the fruit industry, finds the numbers frustrating because new regulations seem to disproportionately affect small growers, even though lawmakers typically express fondness for small farms.

For example, when payroll rules become more complex, growers with human resources departments can more easily comply. New food safety requirements are expensive, so larger farms can better afford to implement them.

"You can't say you like one thing, but hurt that thing with policies," DeVaney said.

Simple economics also drive much of the consolidation, said Karina Gallardo, a Washington State University agricultural economist who writes a production cost and enterprise budget study about the fruit industry every four or five years.

Her latest version is scheduled for release this fall, so she declined to discuss hard figures. But she said she has noticed a spike in the costs of production this go-round. Land prices, trellis systems, equipment, labor and all the other factors sometimes called "inputs" are rising quickly, more quickly than noted in her previous report in 2014.

"That investment is becoming difficult for smaller growers," she said.

Below: Severe Sunburn

Take netting for example, she said. Sunburn netting once was an experimental idea, but it's becoming the norm now as climate changes and research show the advantages for sunburn-sensitive varieties such as Honeycrisp.

![]() The English Apple Man Comments!

The English Apple Man Comments!

In Europe growers have adopted hail netting to combat the devastating effects of hailstorms, but with higher temperatures sunburn damage has caused serious damage. In Britain we are used to losing some Bramley apples with sunburn on exposed fruit in high summer, but the problem is becoming more prevalent, especially in Europe where record temperatures have caused serious losses.

Below: Sunburn damage pictured by The English Apple Man in Belgium caused by temperatures in excess of 41 degrees C lasting a few days.

Labour prices also have spiked. As domestic workers become harder to find, more growers are using the H-2A program, which typically adds about 25 percent to labour costs, she said. Growers who use H-2A workers must pay the federally mandated Adverse Effect Wage Rate, or AEWR, for contracted and local workers. In 2016, the AEWR was $12.62 per hour. This year, it's $15.03. That's a 20-percent jump in three years. Growers who don't use H-2A have to keep pace with their pay rates to compete for workers, as well.

Big stores and small towns

Desmond O'Rourke, a global tree fruit market analyst from Pullman, Washington, said consolidation among retailers is part of the explanation. Bigger grocery chains typically purchase from a few large suppliers that deliver apples 12 months a year. That prompts packing firms to partner under unified sales firms. In the 1980s, Washington had about 100 sales desks; today, about 10.

Those big stores, such as Costco Wholesale Corp. and Walmart Inc., demand a lot from their suppliers, often holding their own audits for food safety, worker treatment and environmental concerns. Then, the global industry's shift to proprietary varieties leaves small growers out. Companies that own rights usually want to deal with larger, more capitalized farms that can efficiently produce the required volumes to meet commercialization goals.

O'Rourke recalls packing sheds up and down the Columbia and Okanogan rivers through North Central Washington. "Virtually all of those are gone and so is the employment in the community," he said.

The effects go beyond just the farm, O'Rourke said. Consolidation drains rural economies of jobs, influence and a sense of community.

So what about here in Britain?

The story is much the same as in USA. While our apple & pear industry is small in comparison to USA and Europe it has been rationalised dramatically over the last 25-30 years,

The story is much the same as in USA. While our apple & pear industry is small in comparison to USA and Europe it has been rationalised dramatically over the last 25-30 years,

50 years ago the number of British top fruit (apple & pear) growers was in the region of 1,500 while today it is circa 150!

The growth of Supermarkets has changed the perspective and they dominate 'top fruit' sales with 80% of all 'home grown' apples & pears now sold in Supermarkets.

Today two very large growers produce close to 50% of all the 'home grown' apples and pears on Supermarket shelves.

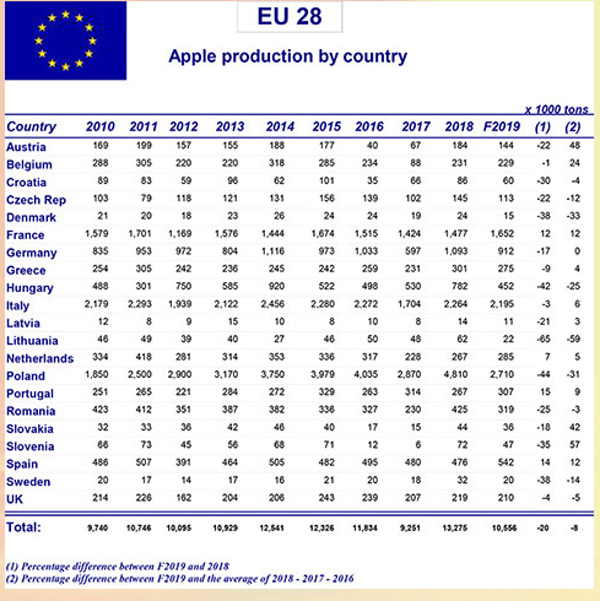

The annual Prognosfruit Conference gathers all the crop data and publishes the table of EU Countries predicted crops for the coming season. It is easy to note that Britain is a very small player, even in Europe with an estimate of just 200,000 tonnes - miniscule when compared with Poland (2,710,000) Italy (2,195,000 and France (1,652,000) .

There is no doubt that the intense competition between the Supermarkets will continue to intensify and the pressure on the growers to continue cutting costs will reduce the numbers of growers further with production polarised between a few very large growers.

What about the small growers who cannot afford to supply Supermarkets?

The English Apple Man predicts there will always be a place for the small volume grower as long as they can serve the consumer directly. There are many well established farm shops, albeit they may not produce their own produce, but are an outlet for small growers in their locality.

The cost of supplying a Supermarket is high and leaves a small margin. The added costs of meeting all the Supermarket specification, and this is not necessarily the visual appearance of the fruit, but the many accreditations over and above the basic food safety requirements. The constant changes in packaging and the labour saving equipment necessary in a large packhouse supplying Supermarkets can only be justified by large volume throughput.

So if the small grower can sell direct to the consumer, the costs are lower and this often allows a price which is lower than the price required for a Supermarket to deliver a meaningful profit for the retailer and return a sustainable price to the grower. The opportunity for the consumer to meet and talk with the grower is a great experience for both parties.

One of the great examples in serving the consumer directly is Chegworth Valley in Kent.

25 years ago this family were trying to serve a major Supermarket chain, but could not compete with the large growers. The answer was to change and deliver direct to the consumer through farmers markets and on the success of this established shops of their own in London.

Below: From the Chegworth Valley website

Chegworth Valley is a family owned and run fruit farm situated in the heart of the Kent countryside, not far from the village of Harrietsham. Established by the Deme family in 1983, the farm had originally been a dairy farm as part of the Leeds Castle Estate.

An initial planting of around 15 acres of apples and pears was planted in the mid 1980's with soft fruit such as raspberries and strawberries following during the early 1990's.

To begin with this was supplied to major supermarkets and wholesalers, whose focus was on perfectly sized & shaped fruit, rather than the taste and quality.

It soon became clear that this was not the way in which the family wanted to work and so the change to supplying direct to the customer and to independent shops and retailers began!

Click on Useful Links on The English Apple Man website for a list of Farm Shops visited by The EAM.

In East Anglia Lathcoats Farm is a well established business with a family history of more than 100 years which offers more than 40 varieties grown on the farm for consumers to 'try and taste' before purchasing!

In The Sussex High Weald another well established fruit farm growing and selling a wide range of apple varieties (and pears, stone fruit as well) and award winning Apple juice made on the farm. Ringden Farm Bought by Ben Dench in 1963 and run by Chris & Lesley Dench since Ben died in 1978. Now growing with their son John Ringden is a fine example of selling direct to the consumer.

Beyond Ashford in Kent on the North Downs 'on route' to Canterbury the Fermor family is another producing and selling direct to the consumer: Perry Court Farm

From the Perry Court website: "Our family have been farming for as far back as anyone can remember, in fact the name Fermor was a medieval job descriptive surname for farmer with pre 10th century!

From the Perry Court website: "Our family have been farming for as far back as anyone can remember, in fact the name Fermor was a medieval job descriptive surname for farmer with pre 10th century!

It was grandfather Lionel (aka Growly Grandpa) who bought the current Perry Court Farm site on the 1940's and it has been expanded over the years by his son Martin and then his grandson Charles.

Two innovative products introduced by Perry Court are: Fruit Crisps and Fruit Bars developed by Charles (Charlie) Fermor.

That is all for this week

Take care

The English Apple Man