Gosh, it's coming round fast, Christmas that is!

So little time and lots to do!

From time to time, The English Apple Man takes a look at what is going on in other major fruit growing countries.

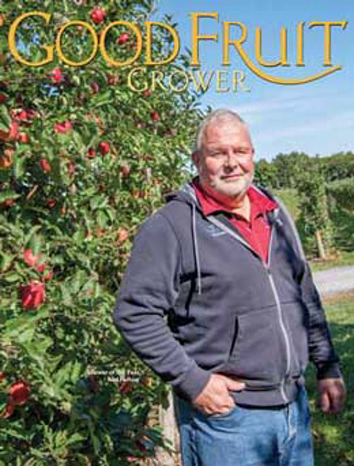

![]() This week an article by Kate Prengaman in The Good Fruit Grower magazine caught my eye!

This week an article by Kate Prengaman in The Good Fruit Grower magazine caught my eye!

Kate Prengaman

Regular English Apple Man readers will be aware of my visit to the late 1800's and the underlying message of how quality is always preferable over quantity, although high yields of quality fruit make for a more profitable existence!

This week The EAM Journal highlights an excellent article in 'The Good Fruit Grower' about an award winning grower who has embraced a 'profit-driven focus on precision horticulture'

Rod Farrow, the 2020 Good Fruit Grower of the Year, is known for his profit-driven focus on precision horticulture, pioneering super spindle systems in New York and for his service and leadership in the apple industry globally.

Rod Farrow, the 2020 Good Fruit Grower of the Year, is known for his profit-driven focus on precision horticulture, pioneering super spindle systems in New York and for his service and leadership in the apple industry globally.

Everyone said you couldn't grow super spindle orchards in New York, because unlike in the arid but irrigated West, you can't just turn off the water to control vigour.

But fresh off a visit to British Columbia, where growers were transitioning to super spindle to increase yields, Rod Farrow decided to give it a try in 1996, with the help of low-vigour Bud.9 rootstocks. It worked so well that by 2001, that's all he had planted on the 425 acres he managed for Lamont Fruit Farm in Waterport, New York.

That's eight times as many trees (per acre) as we were planting, but it didn't make it more work, it made it less work," Farrow said. "It's managing it on a scale that's visible. It's hard to look at a tree with 500 apples and have anybody make sense of it."

What became visible to him was the close relationship between crop load, size, quality and profit potential. For the next 20 years, Farrow's pursuit of precision and profitability pushed him to the leading edge of apple growing. His path to get there was anything but traditional:

Rod Farrow was born and raised a city boy in Ipswich, England. Luckily his first accepted job application as a 13 year old was on a local apple farm 4 miles outside Ipswich where he learned to love working outdoors with plants. After graduating high school and completing a one year exchange living and working on a fruit farm in France, Rod decided that the "school of hard knocks" was for him and he took off for 3 more years working around the world on fruit farms in New York, eventually settling with his family in Western New York to work for prominent orchardist George Lamont, who sold his operating company and orchards to Farrow when he retired.

That unusual path produced a grower who thought a little differently - comfortable questioning conventional wisdom and preferring to crunch his own numbers to maximize the profit on his apple acreage.

What stood out to a young farmworker in the 1990s: While every other manager was talking about quantity, Farrow talked quality. Twenty-five years later, that's still what they talk about, said Jose Iniguez, Farrow's long time farm manager turned partner.

One of the earliest and enduring lessons he learned working for Farrow is that "if you learn something and you don't pass it on, what is the point?" Iniguez said. "Rod has always been an open book to the world."

For that generosity of time and insight, along with his leadership in precision horticulture, new varieties and technology, the Good Fruit Grower's advisory board has recognized Farrow as the 2020 Good Fruit Grower of the Year.

He helps people envision greater profitability through maximizing returns, rather than cutting costs, and he focuses on precision management to achieve those higher crop values," said Terence Robinson, Cornell University fruit crop physiologist. "He's the best grower we have in New York, maybe even in the entire U.S."

He sold Lamont Fruit Farm, his farm operating company, to his partners, Iniguez and Jason Woodworth, to "retire" earlier this year. But Farrow continues to work on orchard development with his partnership in Fish Creek Orchards and with Fruit Forward, a group focused on running variety trials in the Eastern U.S., along with research and technology collaborations.

Data-driven precision

Farrow planted his first super spindle trial in 1996, but he credits the Labour Day storm of 1998, which blew nearly all the apples off the trees, with inspiring his passion for precision horticulture.

Financially, the situation was bleak for Lamont Fruit Farm, where Farrow was working as farm manager, but it also gave him an opportunity to buy into the business and establish himself as the successor for George and Roger Lamont. All around him, farms were trying to diversify their way into better financial shape.

"I thought, well the only thing I know how to do really well is grow apples," Farrow said, recalling the time he took on debt to buy into a business with a negative value. "So, I just have to be really good at growing apples."

He dove into the data from the packing house Lamont has a partnership in, Lake Ontario Fruit Co., trying to understand the highest potential value for each variety. For example, 88 count Galas returned $6 more to the grower than 100 count.

"It was a real eye-opener to me that yield wasn't the only answer," he said. "Not many people were thinking about that, but for Galas it's a potential $20,000 gross back to the grower. That's what became key to our success: shooting for the maximum potential income."

In 2016, while speaking at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association's annual meeting, Farrow shared a chart of Lake Ontario Fruit grower returns on Honeycrisp. The graphic showed the spread between the top 10 percent of growers compared to the average: That year, the top growers were making more than $6 more per bushel than average, and the top grower made $15 more.

Such information enables growers to benchmark themselves to their neighbours.

"I'm trying to inspire other growers," Farrow said. "You have to know what it pays to grow."

Sharing his approaches to making more money fits with Farrow's belief that rising tides lift all boats, said Kaari Stannard, president of New York Apple Sales and Farrow's business partner in Fish Creek Orchards and Fruit Forward.

"The beauty of Rod is that he is so open and puts the industry first," she said.

Belw: left; Rod Farrow and right; Snapdragon apples - colour comparison

Super spindle success

When Farrow first saw a super spindle orchard, he thought: "Ah-ha! This is how you grow beautiful apples," he said.

He's quick to say that it's the best for him, not necessarily for everyone, but the simplicity of the system makes it easier to precision prune, thin and understand.

"It's a lot easier to grow uniform apples with uniform trees," he said. "We just have spurs and not much growth, so you are not dealing with wasted energy - 90 percent goes to the crop."

The establishment costs for 2,000 trees per acre puts off many growers - Farrow credits the on-farm nursery for making it viable (See "Success starts in the nursery") - but in general, he's not afraid to spend money to make more money.

Farrow's regular participation in the Fruit Farm Business Summary - an annual effort by Cornell Cooperative Extension to help growers benchmark their input costs and incomes - shows that Lamont Fruit Farm almost always had the highest costs per acre. But it also usually had the lowest cost per dollar of income, Farrow said.

That's a different perspective than that of many growers who look to cut costs first to increase profits, Robinson of Cornell said. "He was invaluable to our work to make the case that there was money on the table that we don't capture with our looser orchard management," he said.

That philosophy extends to technology, of which Farrow is an early adopter. His planar orchard rows are well-suited to mechanization, vision and, eventually, robotic harvest. At the moment, however, he's more interested in innovations that can improve the crop value rather than just cut labour costs.

"Our H-2A workforce are incredibly efficient, reliable, nice people. It's going to be hard to beat them," he said. But he's excited about enhancing workers' abilities, whether it's a vacuum-assisted harvest platform or a new research effort that taps computer vision systems to do bud counting, thereby making workers more efficient and accurate when pruning.

(The H-2A program allows U.S. employers or U.S. agents who meet specific regulatory requirements to bring foreign nationals to the United States to fill temporary agricultural jobs.)

When it comes to technology, Farrow believes spending money to improve crop value pays off. Take, for example, this leaf blower, which the farm just bought this year, running in a SnapDragon block to improve color. For an apple that's returning $30 a bushel to the grower, "you only have to change one apple per tree" from Fancy to Extra Fancy with extra color to justify the cost of reflective mulch ($500 per acre), Even at the by-hand de-leafing cost of $1,200 an acre, the colour returns paid off, Farrow said, but he puts the cost of the machine, which isn't quite as good as hand labour, at under $50 an acre.

Team effort

Looking back over his career, Farrow credits his success to the chance of working with the right people at the right time. He discovered his love for orchards as a teenager, while looking for a part-time farm job within biking distance from his home in Ipswich, England.

His first boss, Dan Neuteboom, connected him to orchardists in France, where he went to work for what was supposed to be a gap year; Farrow had such a great time, he decided to forgo college and find another orchardist mentor. George Lamont had recently been to visit Neuteboom, so Farrow used that as an introduction and invited himself over. He and Lamont hit it off.

But Farrow still had traveling to do, so he leaned on more connections to work for orchardists in New Zealand, where he met his wife, Karyn, and then on to Japan. But the opportunity to work for Lamont - and the cheap farmland prices - lured him, Karyn and their young daughter back to New York in 1986.

Those early mentors shaped his approach for the rest of his career, Farrow said: "Part of what made me so open is that everyone was so willing to share with me."

Lamont, who died this spring at 83, modelled collaboration as a progressive grower, industry leader and research partner as New York moved into fresh-focused production. Farrow "takes the term grower - collaborator to a new level," said Karen Lewis with Washington State University Extension.

"He helps identify the researchable questions, puts up the resources and trees, and keeps a keen eye on the experimental design and methodologies so there is confidence in the results," she said. "I am better at my job because I have been on the receiving end of his generous gifts of time, leadership and knowledge."

Relationships define how Farrow talks about his success. The grafting and tree production techniques he learned from Mike Argo of Washington made it financially feasible for him to take chances on new varieties.

Mechanization innovations by JJ Dagorret, also of Washington, helped his farm stay efficient in the face of growing labour challenges. A collaboration with former Stemilt horticulturist Dale Goldy built the success of the SweeTango program. He gained insight into technology and industry education by working with Lewis on the IFTA board, and into orchard infrastructure through conversations with Cornell's Robinson as they both pursued the most profitable systems for New York.

The most important relationships are those forged on the farm.

"We are so lucky that Jose came to work for us. You can't put a value on someone who can put 120 people in the position to be successful and provide them the right kind of working conditions and the ability to always be efficient," Farrow said. "We empower people. Anybody that shows any ability gets promoted and asked to do more, and they keep rising."

It's a sentiment he learned from Lamont.

That investment in people is now paying off over generations, Iniguez said. Many of the farmworkers who worked for Lamont Fruit Farm now own local businesses: restaurants, stores and farms. "Besides the farm, he taught us how to manage money, to think outside the box, to stay here and build," he said. "That's a legacy Rod's going to leave."

Looking back on the people that shaped his career, Farrow encourages young growers to invest their time in making connections.

"The worst thing a 20-year-old can do now is stay home on the farm," he said. "A lot of camaraderie is a secret to success in our industry.

by Kate Prengaman The Good Fruit Grower

The English Apple Man would like to thank Kate for her excellent article and encourage readers to check out The Good Fruit Grower Magazine

The English Apple Man is always alert to new technology and the subject of Robotic apple harvesting is of increasing interest.

ROBOTICS

Below: Abundant Robotics staff control start of Robotic Harvester and load an empty bin onto the robot. It will have the ability to swap bins automatically when commercialized.

Israeli company FF Robotics continued improvements on its robotic picker, which uses multiple arms with pronged "fingers" to grip, twist and pull fruit from trees. The new FF Robotics machine is narrower, while the 12 end-effector "hands" have new movement capabilities intended to pick apples more cleanly.

Below: FF Robotics apple harvester

![]() That is all for this week, next Friday is Christmas Day so The Journal will be published on Christmas Eve!

That is all for this week, next Friday is Christmas Day so The Journal will be published on Christmas Eve!

Take care

The English Apple Man