Regular readers of The English Apple Man, will be very aware of the rapid changes in apple production systems over the last few years.

While it took some time for 'very high density' planting systems to establish here in the UK, intensification was advanced in Europe, particularly in Belgium and Holland.

Below: 2 Dimensional tree management

Over the last 2-3 years, technology has transformed the management of apple orchards, allied with very narrow (2 dimensional systems) and the creation of 'digital orchards' enabling monitoring of temperature, light interception, leaf nutrient status, moisture and an increasing range of measurements allowing the fruit grower to tweak the needs of the tree down to an individual level.

Over the last 2-3 years, technology has transformed the management of apple orchards, allied with very narrow (2 dimensional systems) and the creation of 'digital orchards' enabling monitoring of temperature, light interception, leaf nutrient status, moisture and an increasing range of measurements allowing the fruit grower to tweak the needs of the tree down to an individual level.

The use of drones to map orchards down to individual trees, the introduction of sophisticated orchard sprayers capable of delivering pre planned quantities of protectants to individual trees, indeed to 3 selected zones on each individual tree is transforming the way orchards are managed.

As someone who has spent more than 60 years involved with fruit growing and in particular apples, I marvel at the application of new science.

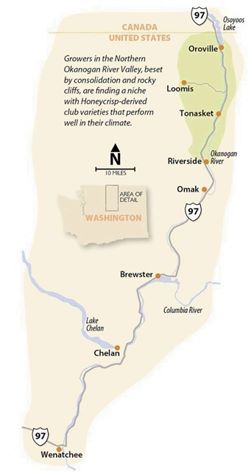

It was then, a surprise to read an excellent article by Ross Courtney in the Good Fruit Grower magazine regarding a family of apple growers in the northern regions of Washington State, who are 'turning back the clock' by growing their apple trees less intensively!

Wide open spaces between trees greet crews beginning a day of SugarBee apple harvest in October at the farm of Richard Werner near Oroville, Washington. Contrary to industry trends, Werner prefers farming freestanding trees at relatively low density because of the erratic soils and slopes in the Okanogan River Valley.

There's plenty of elbow room for Richard and Jill Werner and their crews harvesting SugarBee apples in their orchard north of Oroville, Washington, near the U.S.-Canada border. No ducking under trellis wires or squeezing between leaders.

Even when the fourth-leaf trees grow bigger, workers will still walk all the way around them to harvest.

That's because the Werners prefer farming with amply spaced, freestanding trees on relatively vigorous rootstocks, bucking the industry's sermon promoting high-density fruiting walls as the path to efficiency, modernization and profitability.

"I prefer to farm simply, so that I can work effectively," Richard Werner said.

Richard's favorite orchard layout is 10 feet by 15 feet on Budagovsky 118 roots. That's 10 feet between each tree, in an era when growers sometimes allow 2 feet or less. Bud.118 is among the larger semidwarfing rootstocks, producing trees about 85 percent the size of a seedling, according to the Washington State University apple rootstock guide. As for other traits, the rootstock is cold hardy, moderately resistant to fire blight and can be grown without support.

The Werners cite soil and slope as their two main reasons for sticking to freestanding trees. Soil conditions are erratic in the granite-pocked and glacier-carved landscape of North Central Washington. It's sandy and soft in one area, rocky right next door.

SugarBee a new variety of Malus domestica available commercially only quite recently. SugarBees are an open pollinated apple, whose parentage includes the popular Honeycrisp apple.

SugarBee apples were first discovered in an apple orchard in Minnesota. It was cross-pollinated by a bee between a Honeycrisp apple and another undetermined variety. Mr. Nystrom, the owner of the Ocheda Orchard, found the new variety of apple tree growing among other trees. He took a bite of the large, round, brightly colored apple and discovered it was crisp and very sweet. Mr. Nystrom called the apple "B-51."

SugarBee apples were first discovered in an apple orchard in Minnesota. It was cross-pollinated by a bee between a Honeycrisp apple and another undetermined variety. Mr. Nystrom, the owner of the Ocheda Orchard, found the new variety of apple tree growing among other trees. He took a bite of the large, round, brightly colored apple and discovered it was crisp and very sweet. Mr. Nystrom called the apple "B-51."

Word of this new apple spread to Chelan Fruit Cooperative and Gebbers Farms in Washington state, where growing conditions would be ideal for this new apple. In 2013, Mr. Nystrom agreed to allow Chelan Fresh orchard the growing rights to the new apple, where it was renamed "SugarBee" in honor of the bee that did such fabulous work in choosing which trees to cross-pollinate.

When building their SugarBee block just north of town, they picked rocks out of the ground between each step in the process of replanting from Red Delicious - after pulling out old trees, discing, filling holes and rotovating. "We picked up rocks on this thing five times," Richard Werner said.

Jill's family has farmed this rocky ground for five generations, counting their son, Sawyer, who plans to take over someday and make farming his family's primary vocation, just like his parents. Both Jill and Sawyer are on board with the spacious methods, a topic of conversation around many a dinner table.

"I have pushed the numbers and I in no place see that it pencils out" to plant at high density, said Jill, who has a bachelor's degree in agricultural economics from WSU. The family would have to borrow heavily to pay for an orchard that may have to be removed in 15 years as varieties fall out of favor.

"I know it completely goes against what everybody is pushing," she said. At least, that's the conclusion her family draws in their situation.

Sawyer has the same opinion of the soil and slope as his father.

"To grow and do well with high-density systems, you have to have consistent soil type and you have to have flat land," Sawyer said. "We have neither."

.jpg)

Below: Richard and Jill Werner in their orchards at harvest time

The Werners have tried high-density before and didn't like the results. Trees blew over or snapped at graft unions, Sawyer said. Meanwhile, equipment slipped on the steep hills that characterize the Okanogan River Valley.

The Werners have tried high-density before and didn't like the results. Trees blew over or snapped at graft unions, Sawyer said. Meanwhile, equipment slipped on the steep hills that characterize the Okanogan River Valley.

"Spaced-out trees will carry me through my career as an orchardist," he said.

More than one way

Werner's methods don't just buck a trend, they contradict some of WSU's assumptions about modern tree fruit production.

For most varieties, when publishing routine cost-of-establishment estimates, WSU agricultural economist Karina Gallardo assumes more than 1,000 trees per acre on vertical trellises and Bud.9 or Malling 9 dwarfing roots. Honeycrisp carries the assumption of 1,400 trees per acre.

Gallardo bases those assumptions on interviews with growers, but that doesn't make them mandates, she said.

"My studies are just reference," she said. "They represent realistic cost ranges considering the assumptions made in each study."

There is no "right" way to farm, said Tianna DuPont, a WSU tree fruit extension specialist in Wenatchee.

Each choice has economic advantages and disadvantages, said DuPont, who has not visited the Werners' orchard. Rootstocks must be matched with soil type, scion vigor and labor management goals. Narrow canopy systems allow more light penetration and therefore more uniform color and maturity.

"We don't get paid in bins per acre; we get paid in packs per acre," she said.

Labour management is another consideration, she said. Growers tell DuPont it's harder to recruit workers to large, complex canopies, where they need an artist's touch, compared to high-density orchards, where just a few rules apply. Safety matters, too. Ladder injuries are common.

"There is no single right decision when it comes to choosing a rootstock and training system, but it is critical to run the numbers for the system you are considering," DuPont said.

Dave Taber, another Oroville grower, can vouch for the unpredictable soil in the area. He's gone with high density, overcoming the soil challenges through variable fertilization, pruning and cropping, adjusting his practices row-by-row or even tree-by-tree. But he relates to the challenges the Werners cite: Driving in trellis posts is challenging and expensive.

"It gets sort of funky," Taber said. "It undulates quite a bit and will change three times in 100 yards."

Trade-offs

There is no set rubric for categorizing density, but the Werners' 300 trees per acre would fall under either low density or medium density, depending on who you ask. High density usually runs near 1,000 trees per acre.

The Werners said their spacious choices pencil out because they have invested less up front. Richard knows growers who have spent $65,000 per acre to start a trellised block, while he spends more like $10,000. If something bad happens, such as a freeze or disease, they have less risk. They also keep margins higher with their approach, Richard said, while vertically integrated production companies may be able to profit with a lower margin.

They admit there are trade-offs. Their new trees take two or three years longer to reach full production, compared to their high-density neighbors. And sometimes their freestanding canopies grow too full, resulting in variable fruit maturity and color. In fact, that happened recently to a Fuji block, and they corrected it.

"We got the chainsaws out this year," Richard said.

The family is not opposed to change, overall. They planted SugarBees "to stay relevant," Richard said, even though they have never been a fan of the club model.

They stem-clip the apples because their warehouse, Chelan Fruit, requested it. Richard begins each picking day instructing his workers in the technique and teaching them to pluck fruit straight off the branches to avoid puncture wounds from nearby spurs, a tendency of the variety. He also implores his pickers to move slowly about their work - and even to empty their pockets to avoid bruising.

They stem-clip the apples because their warehouse, Chelan Fruit, requested it. Richard begins each picking day instructing his workers in the technique and teaching them to pluck fruit straight off the branches to avoid puncture wounds from nearby spurs, a tendency of the variety. He also implores his pickers to move slowly about their work - and even to empty their pockets to avoid bruising.

They've been adjusting and changing for decades.

Jill manages the farm finances, and Richard has farmed full time since 1990, when he retired from teaching.

During that time, the family has changed the business from all apples with a weeks-long harvest window to a 200-acre diversified fruit production company with apples, cherries and pears and a harvest that stretches over months.

For them, the methods have worked - "We've been pretty successful," Richard said.

Ross Courtney is an associate editor for Good Fruit Grower, writing articles and taking photos for the print magazine and website. He has a degree from Pacific Lutheran University.

Ross Courtney is an associate editor for Good Fruit Grower, writing articles and taking photos for the print magazine and website. He has a degree from Pacific Lutheran University.

Good Fruit Grower magazine was established in 1946 and is eagerly read by orchardists and vineyardists worldwide. It covers the growing, packing, handling, marketing and promotion of tree fruits (apples, pears, cherries, apricots, peaches, nectarines and plums), as well as juice and wine grape production. The magazine is published in the Pacific Northwest, in the heart of one of the world's top tree fruit and grape growing regions.

Click on The Good Fruit Grower Magazine to read more about their coverage of apple growing in North America.

The English Apple Man Comments

Progressive growers worldwide have sought out Club varieties delivering higher net home prices. They have also developed intensive growing 'fruit wall' growing systems. To make money out of mainstream varieties: 'Gala, Braeburn' et al. yields of 100 tonnes per hectare are common. The most profitable growers in Europe are those growing Pink Lady, the trailblazer of Club varieties. Following that example, Jazz developed in New Zealand and now grown globally has also been very profitable.

Clearly competing in the marketplace with an extensive growing system, with lower yields depends on producing high value apples. SugarBee fits that model.

![]() That is all until next week

That is all until next week

Take care

The English Apple Man